Published

LAST MOVIES

LAST MOVIES – XXX EDITION

Last Movies is the debut collection of writings by STANLEY SCHTINTER, remapping the first century of cinema according to what a selection of its cultural icons saw just before they died.

Published as part of Tenement Press’ infinite “Yellowjacket” series, purge.xxx has produced a limited edition, big-black, hard-back, glow-in-the-dark version available exclusively in 2023: through our website, and at events.

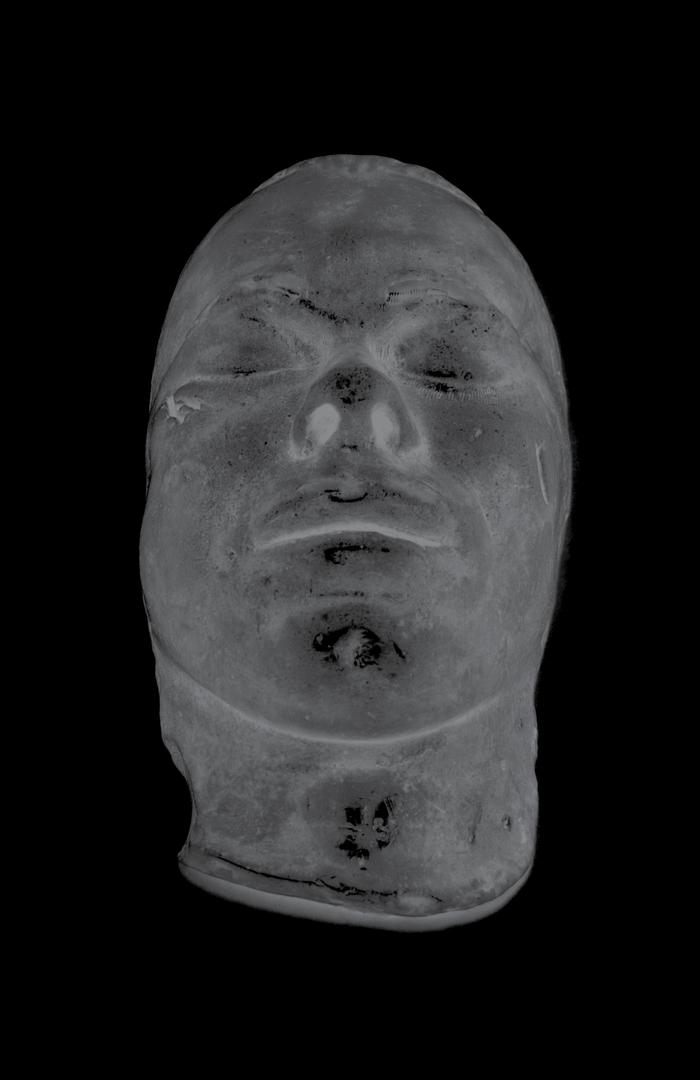

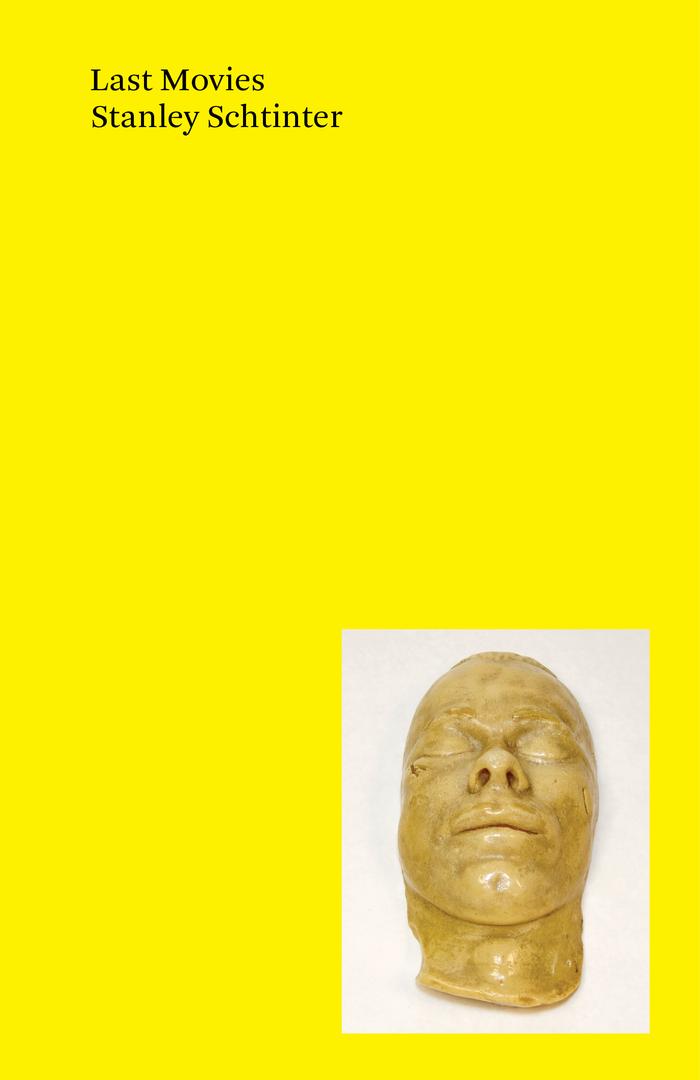

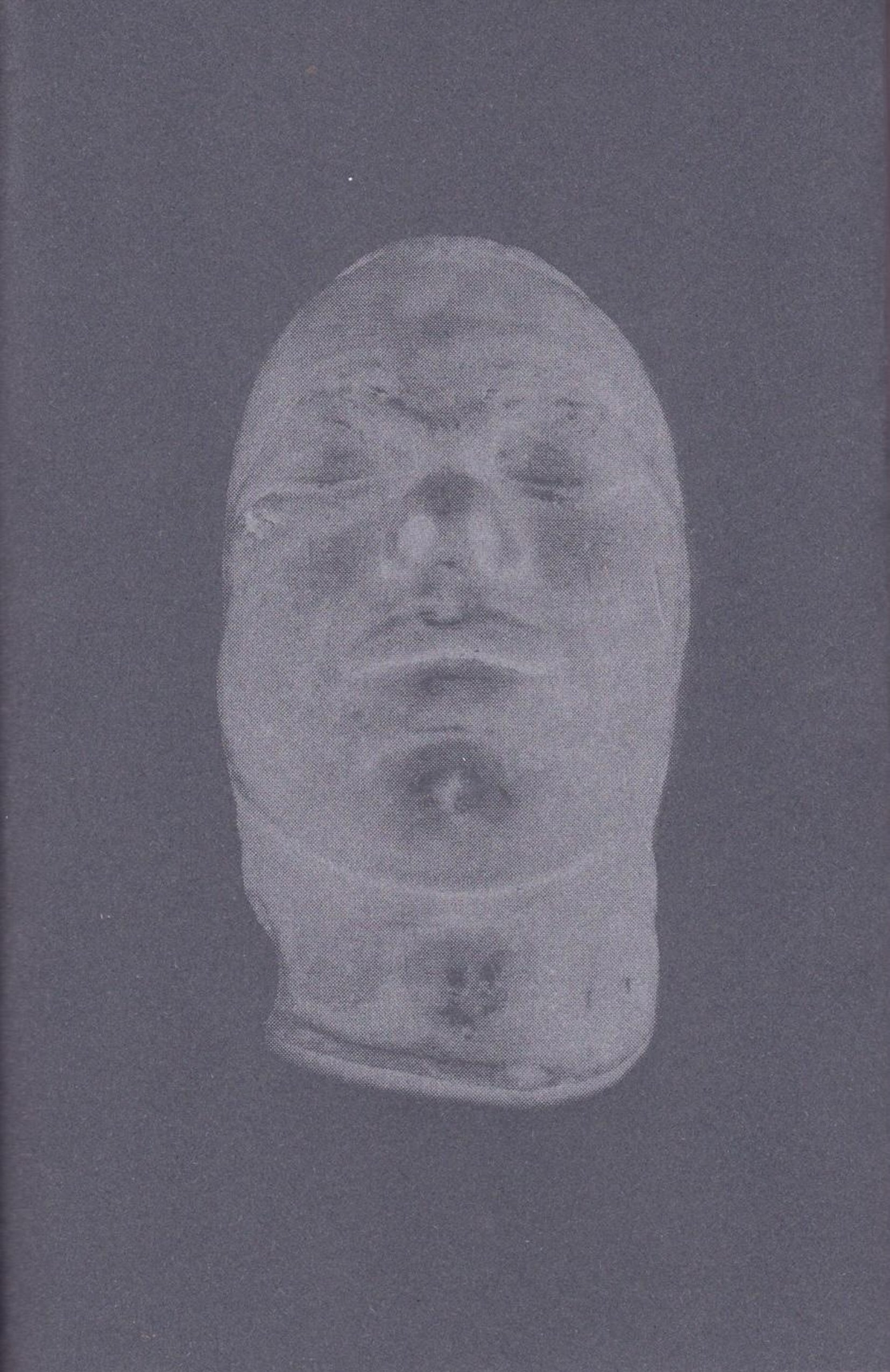

The face on the dustjacket is JOHN DILLINGER’s death-mask, taken by the FBI after his murder.

*

LAST MOVIES – A-Z “CAST” EDITION (26 UNIQUE COPIES)Housed in a huge, black box, the A-Z “cast” edition is also produced by purge.xxx. Each copy is unique, taking a letter from the alphabet and assigning it to one of the characters in the book in the order they “disappeared,”, ie. KAFKA = A; GODARD = Z. This will be issued according to the time of the order: the first gets A, and so on.

Included in this edition:

(1) x1 foil frontispiece depicting one star from A-Z (FRANZ KAFKA to JEAN-LUC GODARD) with forged signature by SCHTINTER [numbered]

(2) x1 hardback with glow-in-the-dark dustjacket [numbered and signed by author]

(3) x1 softback / “yellowjacket” standard stickered issue by Tenement Press [numbered and signed by author]

(4) x1 audio triple-cassette copy of SCHTINTER reading the book (purrrrrj030) [numbered and signed by author]

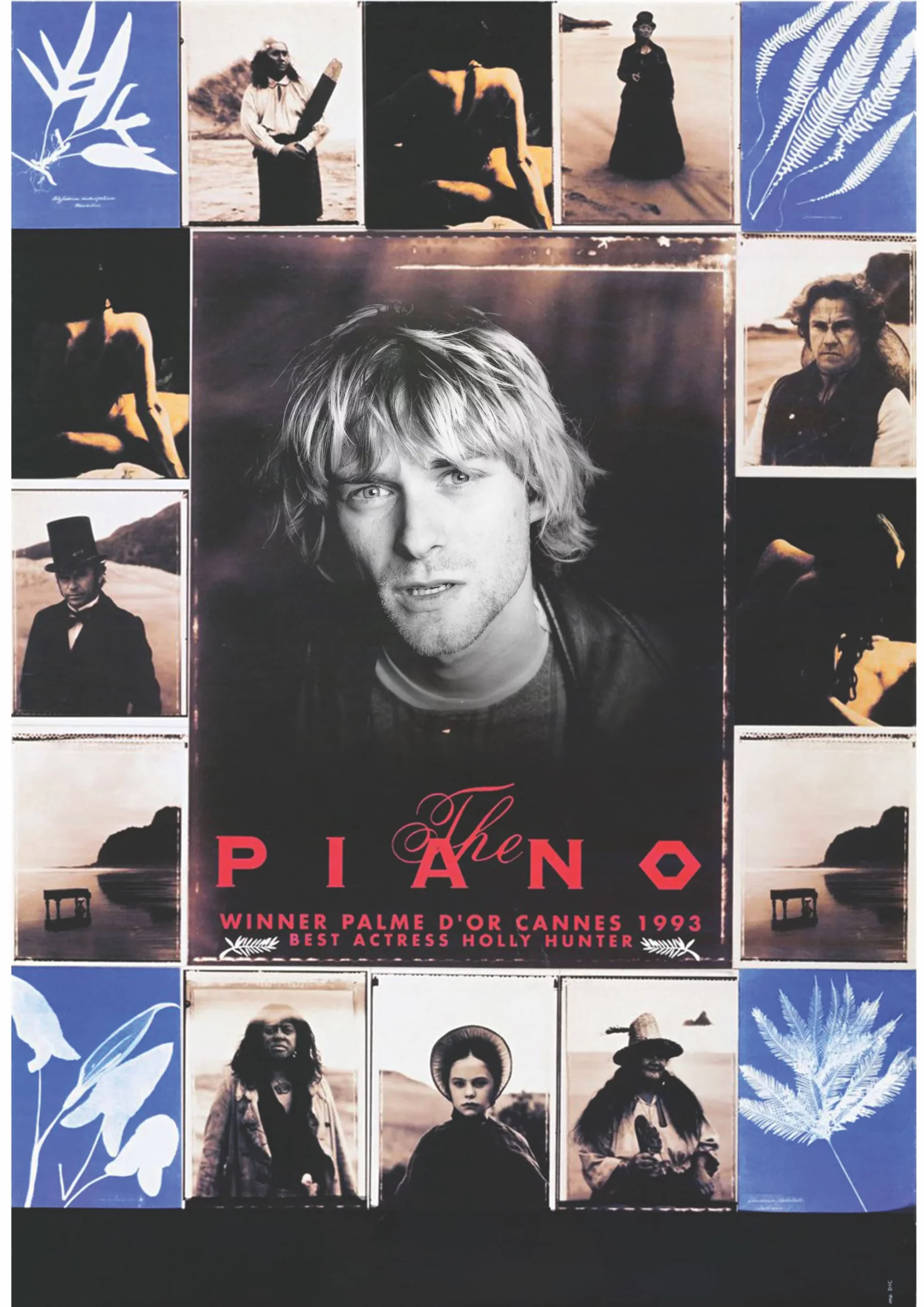

(5) 5xA3+A4 printed posters with original movie poster artwork overlaid with image of Last Movies cast member (eg. JFK on From Russia with Love), [numbered, crossed and stamped by SCHTINTER]

(6) x1 ticket stub from NYC launch event in November 2023 [numbered and crossed]

(7) x1 A4 booklet IAIN SINCLAIR “The Laughing Policeman: on Stanley Schtinter’s Last Movies” (original cut for Sight & Sound November 2023 issue)

(8) x1 A4 booklet DOMINIC J. JAECKLE “Disambiguate My Journey for Me or Chance Me My Destination” (on Last Movies) [numbered and signed by author]

(9) x1 A3 hard black box to encase and protect all elements

(10) x1 personalised, numbered, stamped & signed certificate of ownership / contents

A durational artwork, moving-image experience, and parallel publication, Schtinter’s Last Movies—the tenth “Yellowjacket” from Tenement Press—remaps the century of cinema according to the final films as watched by a selection of its icons …

In the morning they throw men to the lions and the bears;

at noon, they throw them to the spectators.

Seneca the YoungerA set of A3 posters as adulterated companions to Stanley Schtinter’s debut collection, Last Movies, and as partner pieces to a roving programme of screenings and events that accompany and contradict the apparent fixity of publication (death is not the end, et cetera).

Stanley Schtinter, Last Movies (A book of endings.)

What is a society that values nothing more than survival?

Giorgio Agamben

The cinema can kill, just like anything else.

Louis Malle

A furnace of facts in our age of entirety;

a compendium of endings from the artist …Stanley Schtinter’s debut collection, Last Movies, is an extensive and exhaustive research project. A holy book of celluloid spiritualism and old canards that—questioning and reconfiguring common knowledge—recasts the historic column inches of cinema’s mythological hearsay into a thousand-yard stare of a book. An excoriation of the twentieth century (and our dance into the twenty-first), Last Movies antagonises the possibility of survival in an age of extremity and extinction, only to underline the degree of accident involved in a culture’s relationship with posterity.

Here, we’ve a book in which Manhattan Melodrama, directed by W.S. van Dyke and George Cukor, is seen by American gangster John Dillinger, only for him to be gunned down by federal agents upon leaving the cinema. In which George Cukor watched The Graduate, and dies thereafter. In which Bette Davis—given her break by Cukor—watches herself in Waterloo Bridge (the 1940 remake Cukor had been meant to direct), before travelling to France and failing to make it back to Hollywood. In which Rainer Werner Fassbinder watches Bette Davis in Michael Curtiz’s 20,000 Years in Sing Sing, and suffers the stroke that kills him. In which John F. Kennedy watches From Russia with Love at a private ‘casa-blanca’ screening prior to the presidential motorcade reaching Dealey Plaza; in which Burt Topper’s War is Hell exists only in a fifteen-minute cut, considering this is as much as Lee Harvey Oswald would have seen at the Texas Theatre in the wake of JFK’s killing.

Like Hermione Lee “at the movies,” and redolent of the works of Kenneth Anger, Schtinter’s Last Movies is enamoured by the ludicrousness of a swan song that lingers on in a world still trying to sing. Rather than a book dedicated to the effects of cinema on society, this is a collection of writings predicated by a dedication to cinema. Last Movies is a love letter to those that’ve lived (and died) amidst the patina and glow of cinema’s counterpoint to life (as lived) via a haphazard index of twenty-eight of its notable audience members.

This edition also includes programme notes (from a marathon screening), ‘Towards the Last Movies’ by Erika Balsom, an afterword / last word(s) from Nicole Brenez, & an intermission from Bill Drummond.

Stanley Schtinter, Last Movies (A limited Tenement & purge.xxx hardback edition.)

A special, limited edition hardback edition of Schtinter’s debut collection, carrying a “glow-in-the-dark” iteration of John Dillinger’s death mask on its cover. Available November through New Year’s Day, 2024. Order from purge.xxx to receive an accompanying cassette carrying an unabridged reading of Last Movies by the author.

As artist-curator Stanley Schtinter puts it, Last Movies allows us to “see what those who no longer see last saw.” This marathon screening of the final films watched by famous individuals brings the medium of cinema into contact with the matter of death. Between the two, there is not the shock of juxtaposition but the bleed of likeness: they curl cosily around one another like the intimate friends they are. There is the cliché, as familiar as it is unverifiable, that when your time is up your whole life flashes before your eyes, like a film experienced in a dilated instant. (Does this mean these last movies are in fact penultimate movies?) And then there are the many evocations of the cinema as a modern memento mori: it is “death at work” (Cocteau), “change mummified” (Bazin), “death twenty-four times a second” (Mulvey). The medium brings us face to face with finitude, not because the stories it tells about death are particularly compelling but because it captures ephemeral traces of life and reanimates them forever after, infusing the petrified past with spectral vitality. In 1929, Jean Epstein ventured that “death makes its promises via the cinematograph.” Schtinter’s epic undertaking yokes these vows to the moment of their fulfilment.

Normally, the flickering screen only quietly whispers vanitas vanitatum. This murmur likely turned into a roar for Bette Davis when, in 1989, aged 81 and sick with cancer, the star watched the last movie of her life, one of her own: James Whale’s Waterloo Bridge (1931). In it, she has only a small role, sixth billing in the credits. Yet she is nevertheless there, her youthful self preserved across the decades like an insect in amber. Among Schtinter’s selections, Davis’s last movie stands out for its apparent deliberateness. It is as if the ailing star sought to at once defeat and welcome death by revisiting one of her earliest on-screen appearances. Of course, it might have been just another professional obligation: Davis was receiving an award from the San Sebastian International Film Festival, where a Whale retrospective was also taking place. She probably had to be there, like it or not. Who knows if she knew it was to be her final visit to the cinema. But wait – was Davis even at the projection? It is possible, probable even, but the historical record cannot confirm it.

Last movies tend to be like that: they aren’t chosen in the way that a last meal would be chosen by a prisoner awaiting execution. And depending on the circumstances, their lastness can throw up some resistance to verification, plunging curator and audience into the pleasures and perils of speculation. Death is a certainty – but the moment of its arrival, for most at least, is anything but. A last movie is just another unremarkable beat in the rhythm of life until the reaper visits. Then a sea-change occurs; retroactively, the movie becomes a crepuscular artefact it had never before been, coloured by the shadow of death’s imminent approach, bound forever to the end of an illustrious life. Even though Schtinter includes deaths that were planned (the Heaven’s Gate cult) and deaths that were perhaps somewhat anticipated (Bruce Chatwin), his endeavour is a macabre tribute to the curiosity and horror that this radical contingency inspires. As the many hours of the programme pile up, questions might pop into the viewer’s mind: is the lastness of these last movies significant in any way or is it a mere fact? Is it but a plausible fiction? What do these films reveal about the lives to which they belong? Perhaps something; likely nothing. Each title sparks a desire for meaning – each last movie is an incitement to discourse, a story to be told – and each equally allows the threat of meaninglessness to run riot.

Last Movies brings together its selections by the force of an external event, one which bears not on the films themselves but on little-known details of their exhibition histories, and then orders them not according to any curatorial vision but by date of disappearance. It abandons all those calcified criteria most frequently used to organise cinema programmes: period, nation, genre, director, star, theme. Nothing internal to these films motivates their inclusion, their “quality” least of all. Although Schtinter can choose a death to research, the title to be shown is dictated by history. This is all to say that Last Movies embraces chance, an avant-garde strategy its orchestrator has been known to marshal in previous undertakings.

And so it should be for a programme about death. The tenacity of the “life review” flashback as a trope in fiction films could be attributed to the fact that people who have had near-death experiences claim to have encountered the phenomenon. It is more likely that this convention endures because it satisfies a reassuring fantasy: that life will ultimately attain coherence. The fantasy of that “last movie” is undone by the reality of Schtinter’s Last Movies. They are often random and in large part unchosen; they throw significance into crisis and demand acquiescence to externality. They are, in other words, like death itself.

Erika Balsom, 2023